Democracy Seminar: The Empire Strikes Back

The imperial formations and colonial relations framing Russia’s war on Ukraine

Emmanuel Guerisoli is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and History at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

Two months have passed since the beginning of Russia’s second recent invasion of Ukraine. Predictions of the outcome of the conflict have shifted from certainty of a full Russian occupation to a stalemate resulting in protracted war. Uncertainty over probable resolutions mirror myriad causal accounts explaining Russia’s aggressive behavior. Regrettably, almost all such interpretations have ignored long term historical processes and have focused on the events following the fall of the Soviet Union, as if Russia’s relationship with Ukraine only began in 1991 and could just be framed as a conflict between two newly independent nations over post-imperial territories. The reality is that modern Russo-Ukrainian relations are at least 400 years old and have been defined by Russian imperial formation and its colonization of Ukraine. This historical framework is pivotal to properly understand the factors and consequences of this war.

Arguments focusing on NATO or civilizational fractures depend on geopolitical simplifications or ideological rigidities. They misinterpret the long-term socio-historical processes that are crucial to understand the drivers of Moscow’s actions since 2014 and they also ignore the link between those processes and the contextual developments that triggered the latest invasion. The key to understanding the recent events is the historical nature of Russia’s relationship with Ukraine, which is fundamentally colonial; broadly understood as socio-political domination, based on resource extraction and differential citizenship, between an imperial core (or metropolis) and a periphery (or colony).

While colonialism surely explains a lot, it might not sufficiently reveal why the Kremlin decided to carry on a full invasion of Ukraine now instead of in 1994, 2004, 2008, 2014, 2018, and so on. Ukraine is not a military threat to Russia, but it does represent a political challenge in two ways. First, while Ukraine is not yet a mature liberal democracy, it is developing a democratic political system with competitive free elections and an independent judiciary. In this sense, Ukraine stands out among the post-soviet states. Second, Ukraine has, since 2004, endeavored to free itself from its political economic dependency on Moscow. This process accelerated in 2014, after the Russian invasion and occupation of Crimea and the Donbas. Both its democratic system and its independence from Russia are viewed by the Kremlin as existential risks to the legitimacy of their own authoritarian regime, the internal colonial relations between Moscow and non-independent republics, and Russia’s hegemonic domination vis-a-vis other post-Soviet states. A truly sovereign Ukraine is seen as the end of Russia as a great power.

This essay provides a historical overview of the relationship between Russia and Ukraine through the framework of colonialism. Extractivism of raw materials and racialization of Ukrainians, through erasure, are what define Russian imperial formations in Ukraine. While socio-historical processes consist of both ruptures and continuities, the argument presented here relies more on the latter to emphasize the colonial nature of Russian domination and to simplify a truly intricate and complex history. This is most obvious in how the Soviet period gets treated in a monolithic way when, in fact, the USSR’s domination over Ukraine was mitigated after Stalin. Intellectual honesty requires this flagging.

Russian Imperial Formations

Russia is a very peculiar peripheral country, one that exports raw materials and imports technology but that relies on imperial relations with colonial, clientelist, or satellite states for both the extraction of resources and as exclusive markets for their own manufacturing goods. Russia, as a political entity, is best understood as an imperial periphery (or perhaps peripheral empire). Throughout its history, first the Principality of Muscovy, and later Russian Tsardom, its political elite were only able to maintain and extend its power by resorting to the continuous expansion, occupation, and incorporation of adjacent territories to monopolize the Eurasian trade routes of certain commodities into Europe. Extraction of raw materials (slaves, fur, salt, timber, grain, gold, coal, iron, oil, gas) and their export to the European markets allowed Muscovy to accumulate capital for importing European manufactured goods and finance their continuous expansion.

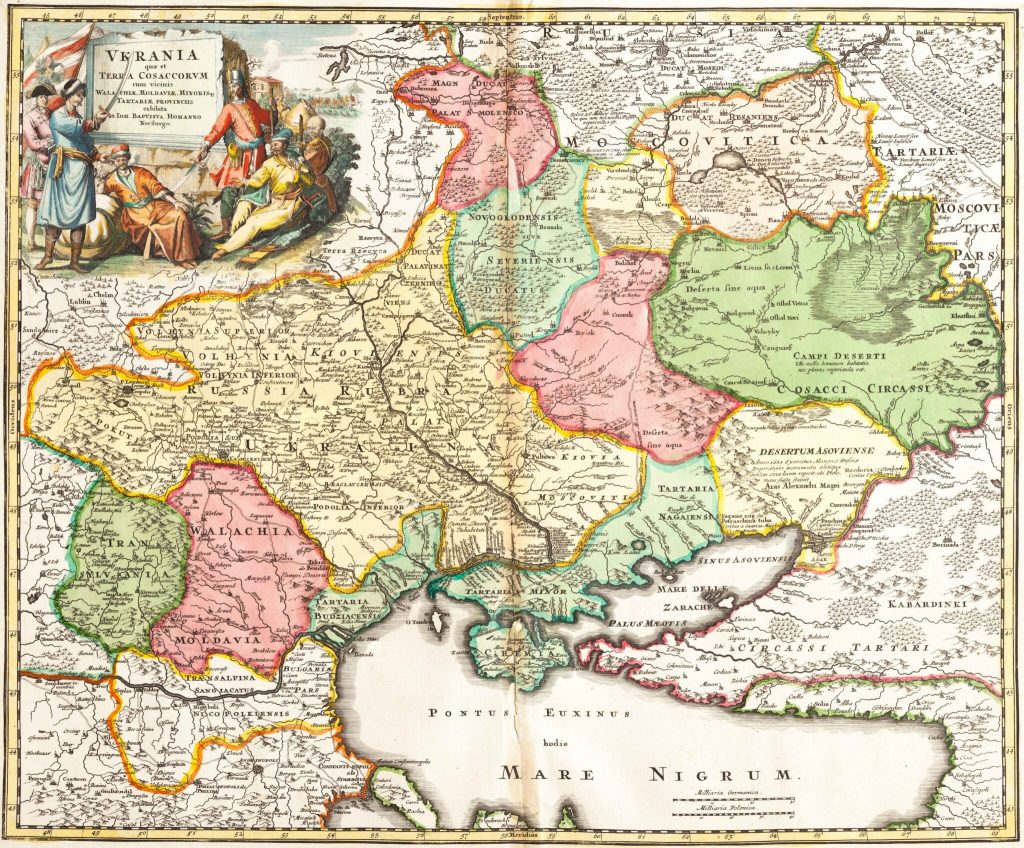

Losing access and monopoly to trade routes would have meant an end to that expansion. Once Muscovy eliminated any competitors from the north and east, it redirected its efforts to access first the Baltic sea and then more importantly the Black Sea. To achieve this, Muscovy imposed a colonial relation of vassalage with the Cossack Hetmanate and later engaged in wars with the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Swedish Empire, securing hegemony in the Baltic. Access to the Black Sea region was achieved after a series of wars against the Crimean Khanate, the Poles, and the Ottoman Empire. Through the imposition of serfdom and the importation of German and Jewish settlers in Ukraine in the 1760s, the Russian empire achieved a monopoly over grain provisioning to Europe. But extraction to accumulate capital for expansion proved to be a deficient model in the mid 1800s.

The abysmal Russian defeat in the Crimean war in 1853-1855, while trying to extend to the Mediterranean, represented a critical juncture that redirected extractivist practices towards financing industrialization to compete with European powers. European investments were crucial for Russia’s economic revival after 1905. Relying on western capital and technology to both industrialize and finance expansion would be a constant until at least 1945 and would once again come to the fore in the 1970s and later after 1991.

From Moscow’s geopolitical point of view, the fall of the Soviet Union represented a historical trauma. The Russian European borders had not contracted to the 1917 but to the 1654 borders, before the incorporation of the Cossack Hetmanate and the transformation of the Russian Tsardom into the Russian Empire. This new status quo delegitimized Russia’s claim to a great power status and reduced Moscow’s relevance in European politics. Relinquishing the “Near Abroad” endangered Russia’s internal colonialism, opening the door for the possible balkanization of the Russian Federation and its eventual breakup as showcased by the two brutal Chechen Wars (1994-1996/1999-2009) for the independence of the Republic of Ichkeria.

The Origins of Russian Colonization of Ukraine: from Vassalage to Settler Colonialism

The historical event that initiates Russian domination over Ukraine, in modern times, is the Pereiaslav Agreement of 1654 that offered the Cossack Hetmanate (precursor to the Ukrainian nation state) protection by Muscovy (precursor to the Russian imperial state) in exchange for allegiance to the Russian Monarch. This treaty marked the official start of Russian expansion into Ukraine and its different interpretations by Moscow and Kyiv respectively have framed their relations ever since.

The Cossack Hetmanate was founded by Bohdan Khmelnitsky during the Uprising of 1648-1657 in the eastern territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Cossacks, alongside Ukrainian peasants and Tatars of the Crimean Khanate—at the time an Ottoman vassal state—started to rebel across present day Ukrainian territory against Polonization policies, which subordinated Orthodox, Protestan, Muslim, and Jewish subjects. The Uprising coincided with the Swedish and Muscovy’s challenges to the Commonwealth’s hegemony in the Baltic and East Central Europe. For Khmelnitsky, the Pereiaslav Agreement had formalized Russian assistance in protecting the Hetmanate independence from Polish tutelage; for Tsar Alexis, it reunited Kyiv’s Rus and Muscovy’s Rus by incorporating the Cossack lands into the Tsardom. As historian Serhii Plokhy shows, the “reunification paradigm” has defined Russian, and later Soviet, historiography of Russian-Ukrainian relations since the end of the 18th century; a Pan-Slavic ideology claiming that Russia’s historical destiny was to reclaim and recuperate the Rus lands lost to Western and Muslim invaders since the times of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054. The point on historiography will become central to frame the current invasion, for now it suffices to say that after 1654, the Cossack Hetmanate was subject to partitions between Russia and Poland and eventually was fully annexed into Tsardom territory in 1709. From 1764 onwards, during the wars with the Ottomans, the Hetmanate was liquidated into the Black Sea under Catherine the Great and the Novorossiya Governorate.

Russia’s colonial domination towards Ukraine has gone through several stages since the Pereiaslav Agreement of 1654. According to Willard Sunderland’s study of Russia’s colonization of the Eurasian steppes, the first period, from 1655 until 1764, was characterized by the transformation of the Hetmanate, called the Zaporozhian Sich, into something in between a vassal state and a protectorate defined by a type of frontier colonialism. While certain Cossack elites had a degree of internal autonomy, Moscow had control over their foreign relations and trade, they were subject to tribute, and they contributed to the Tsar’s army. Being at the borderlands implied that their territory was constantly militarized to carry incursions into the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire, and the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Cossacks were converted into the military expansionist and defensive force of the Russian Empire across the Black Sea borderlands, and their Hetmanate was transformed into a tributary buffer zone.

Loss of autonomy was also felt in the religious and cultural spheres. Starting in 1685, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church began to be absorbed by, what would later become, the Russian Orthodox Church. By 1722 , Peter the Great had named Kyiv an archdiocese and not a metropolitane, effectively ending its autocephaly or ecclesial self-governorship. Just the year before, in 1721, Peter the Great was named All-Russian Emperor, no longer just Tsar, after not only winning the Great Northern War against Sweden but also replacing the Moscow Metropolitane by the Most Holy Synod in Saint Petersburg, exerting state control over all ecclesiastical jurisdictions and authorities of Russia, Ukraine and Georgia. This would inaugurate the Russification policies in the years to come.

The Cossack autonomy was progressively eliminated as the borders of the Russian Empire expanded, leading to a second stage of Russian colonization from 1764 until 1863. During this period, Russia’s colonial relations with Ukraine were set by Catherine the Great during her long reign. Once the Cossacks had fulfilled their military role in the Russo-Turkish War, they became unnecessary and, to avert any more Cossack rebellions, the Sich was finally dissolved in 1775. With the progressive incorporation of the Crimean Khanate, Yedisan, and the right bank of the Dnieper, the Tsarine administratively reorganized the Ukrainian territory into four governorates, including Novorossiya. Furthemore, it promoted a policy of Russification, which besides abolishing regional autonomies, introducing of serfdom, converting Ukrainian Uniate Catholic churches into Orthodox ones, and imposing uniformity in administration through the use of Russian language, included the development of agrarian colonies through the settlement of migrants. Thousands of Germans were “invited” by Catherine the Great to replenish Crimea, Novorossiya, and parts of Western Ukraine. Jews were also allowed to immigrate into what would later be known as the “Pale of Settlement” that covered half of Russian occupied Ukraine, though they were banned from the Russian parts of the Empire.

If during the first stage Moscow’s colonial relation towards Ukraine was characterized by tribute and military service from the Cossacks, the second one consisted of settler colonialism legitimated by an Enlightenment ideology that scientifically administered, pacified, and rendered the territories productive by importing “civilized” populations to effectively farm the black soils and replace the “unruly and nomadic pastoralists” native communities composed of Ukrainian peasants emigres. The conversion of Ukrainian lands from peripheral “wild west” to the center of Russian colonial resource extraction was just beginning.

Imperial Extractivism and Ukrainian Erasure

In the mid-19th century, the increasing relevance of Odessa as an export trading port for goods, among them Ukrainian grain, was one of the drivers for Saint Petersburg’s bid for control over the Danube Delta and the Bosporus Straits. This drive resulted in Russian defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1855) against France, Britain, the Ottomans, and Piedmont. This military shock opened the doors for a series of imperial socio-political reforms such as the emancipation of serfs in 1861 and censorship. However, these relaxations were accompanied by the elimination of all manifestations of nationalist separatism, following the unsuccessful January Uprising of 1863. The third stage from 1863 to 1905 could be defined as assimilationist modernizing colonialism, characterized by the imposition of an “all-Russians” nation policy into Ukraine. This consisted of a series of policies, embodied in the Valuev Circular of July 1863, that banned the use of Ukrainian language and declared its non-existence as separate from Russian.

These anti-Ukrainian directives were legitimized by the emergence, and hegemonization, of particular trends within modern Russian historiography and sociology that considered Ukrainian, and Belarusian nations as Western toxifications of Little and White Russian regional identities within an all-Russian national identity. For Russophile intellectuals, Ukrainian language was, in fact, a Russian dialect and Ukrainian cultural identity was a historical aberration, produced by Austrian imperialism and Polish nationalism with the aim of subverting the Russian Empire. Ukrainians, Belarusians, and “Great Russians” had a common origin in the Medieval Kyivan Rus, the reign of which was truncated by Mongol forces but its remnants had survived and flourished in an independent Muscovy. The Russian Empire’s manifest destiny was to recuperate and reunify the lands and peoples that belonged to Kyivan Rus and protect them from foreign invaders, and purify them from alien influence.

This socio-historical teleology is crystallized by the creation of a triune Russian identity to which Ukrainians, who only existed vis-a-vis Saint Petersburg as “Minor Russians”, were incentivized to assimilate into. Ukrainian identity was not considered inorodtsy, indigenous ethnicity of non-Russian descent with special rights within the Empire, but a fictitious European invention that had to be repressed. Acculturation into the “all-Russian’ ethnos was the pathway to non-discrimination. This triune Russian identity discourse cohabitated with a Russian centered Pan-Slavic ideology that did not negate the existence of other Slavic peoples, unlike with the Ukrainians, but framed their existence within a tutelage mode analogous to Moscow’s submission of the Cossack Hetmanate into vassalage.

Assimilationist policies did not just target Ukrainian literati; the education system nationalized the peasantry as Ukraine became the colonial jewel of the Russian Empire. Once Siberian fur stopped being Russia’s main export, grains took over making Ukraine the source of more than 75% of Russian exports. This led to the rapid industrialization of the region with the construction of railroads and development of metallurgical enterprises, thanks to the rise of iron and coal mining in the Donbas and foreign direct investment. The rapid industrial transformation of Ukraine required the influx of hundreds of thousands of workers; mainly peasants from the Southern Russian provinces migrating to find more productive soil and escape hunger and poverty. Most of them ended up contributing to Ukrainian urbanization, creating an ethnic imbalance between cities and countryside: while half of the urban population was Russian, only 15% of the rural population was Russian.

This demographic disparity reinforced the colonial asymmetries between Russians and Ukrainians. Most of the industrial working class, including artisans, was predominantly Russian, Jewish and Polish. Even Ukrainian peasants that had the opportunity to migrate, preferred to relocate to Southern and Eastern Russia where lands were still available and where there was a modicum of freedom from state repression.

From this moment on until well into the 20th century, Ukraine would become integral to Russia’s, and later the Soviet Union’s, economy. In this sense, suppression of Ukrainian identity was not only useful but imperative to legitimate Russian imperialism. It also prevented any type of movement for national self-determination that could result in an independent Ukrainian state, bolstering Russia’s economic and great power status. This was a lesson painfully learned during the first years of the Soviet Union. The period of 1905 to 1922, could be briefly considered an interregnum of Ukrainian decolonization. Following the Russo-Japanese war and the Revolution of 1905, after which Czar Nicholas II allowed cultural and political liberalization to prevent a state collapse. Many Ukrainians reverted to Uniatism, being able to leave the Orthodox Church without political repercussions. Ukrainian was recognized as a language and its use was no longer prohibited. And new political parties formed advocating Ukrainian autonomy. These reversals set the ground for an independent Ukraine between 1917 and 1922 after the collapse of Tsarist Russia.

Suffice to say that Russian colonial reach was never fully truncated during these years. It continued either through the White Army or Bolshevik occupations, in addition to the German and Austro-Hungarian occupation after the treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918, and the Second Polish republic military intervention in 1919-21. Yet, the brief moments of the internationally recognized Ukrainian Republic, were enough for Soviet Russia to realize how central resource extraction from Ukraine was to its own industrialization process. Even when Lenin had recognized Ukrainian independence he retracted it once German troops evacuated Ukraine following Berlin’s capitulation.

Soviet Extractivism and Ukrainian Extermination

If Ukraine was Tsarist Russia’s ticket to modernization, for Soviet Russia it would be the means of survival. Although Moscow’s colonial relations towards Ukraine during the USSR’s existence went through different levels of oppression, the period between 1922 and 1991 Ukraine could be understood as a fourth stage of colonialism: one purely based on extractivism through genocidal management for the proletarian dictatorship. This characterization is not hyperbolic. The new ideological legitimation of the colonial ruler meant that more ruthless methods had to be employed to achieve not only industrial modernization but communist emancipation through the entire proletarianization of society. In order to achieve this, the Soviet Union needed to outcompete capitalist countries at a very fast pace by emulating their heavy industrialization and importing their technological know-how.

Before addressing the link between Soviet rapid industrialization and colonial Ukraine, it should be mentioned that from 1922 to 1929, Moscow did adopt a policy of accommodation towards its Near Abroad colonies known as korenizatsiia, indigenization, that consisted in the integration of non-Russian subjects into the governments of different socialist republics and the elimination of Russian domination through the respective political and cultural nativizations. Ukrainian communists would be in charge of administering the Ukrainian SSR, and the Ukrainian language would be used for official administration and school education.

Stalin reverted back to Russification by ending korenizatsiia and further centralizing the Soviet Union at the expense of the non-Russian republics. Lenin’s New Economic Policy was abandoned and replaced by two five-years plans that focused on achieving a high degree of industrialization through ruthless extractivism. The Soviet Union was in dire need of technological improvements but lacked capital and was barred from accessing international financing. Therefore, in pursuit of exports to exchange for foreign currency, in 1931 Stalin started targeting the grain resources of Kazakhstan, but particularly of Ukraine, by imposing the collectivization of agriculture on what were mostly small-scale subsistence farmers. The state confiscated their property and forced them to work on state-run collective farms. Prosperous farmers and those resisting collectivization would be labeled kulaks, rich peasants, declared enemies of the state to be deported or just eliminated. By 1932, the Communist Party set exorbitant quotas that Ukrainian villages were unable to meet, triggering requisition campaigns for unfulfilled quotas of seeds and all foodstuff. Ukrainian peasants were forbidden from leaving the countryside, which by then was militarized to prevent people from taking any of the harvest; the theft of any amount of grain was punishable by execution.

This forced extraction of grain led to mass starvation of biblical proportions. In Ukraine alone it is estimated that at least 5 million died due to famine and disease. The 1932-1933 famine in Ukraine is known as the Holodomor: the killing of Ukrainians through a deliberate policy of starvation. This great famine was not an administrative oversight, nor an agricultural catastrophe, but part of a genocidal plan by Moscow for totalitarian colonization of Ukraine. While Ukrainian peasants were starving in the countryside, Ukrainian political and cultural elites in the cities were liquidated. The latter allowed the transfer of Ukraine SSR’s capital from Kharkiv to Kyiv, a city with far less Ukrainians, in 1934. In Red Famine, Anne Applebaum describes how, in addition to designing the starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasants, Soviet authorities deliberately planned and executed the purging, arrest, deportation, and elimination of the cadres of Ukrainian Communist Party and of Ukrainian authors, intellectuals, artists, writers, religious leaders, and any other member of Ukrainian cultural and political milieus. Even Ukrainian communities in Kuban and Kazakhstan were more severely targeted by requisitions and purges than others.

In Kremlin’s view, korenizatsiia had produced internal fractures and centrifugal non-Russian nationalistic forces that threatened the Soviet Union’s ideological and state-formation aspirations. The genocidal recolonization of Ukraine was imperative for the political survival and economic progress of the USSR with Russia at its center. By exporting all possibly available crops in Ukraine abroad, Moscow was able to afford importing technological products and know-how from the United States that were essential for modernizing Soviet industry and military power. Most of such industrialization took place in Ukraine itself with the construction of hydroelectric dams, power plants, metallurgical and machine manufacturing factories, textile mills, and food processing plants. Just as it was during the Russian empire, the Donbas was the industrial heartland of the Soviet Union. The heavy industry in the region was expanded thanks to the starvation of the countryside and the forced labor of those deported. Between 1929 and 1941, Moscow’s statehood completely depended on its colonial regime over Ukraine. What western capitalism took centuries to achieve, through the killing and enslavement of millions, Soviet communism, or Russian-state capitalism, accomplished within barely a decade, using similar measures.

This rapid industrial development made USSR militarily capable of conspiring with Nazi Germany to invade Poland in 1939 and later “recuperate” the territories lost after Brest-Litovsk including the occupation and annexation of the Baltics, Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Keralia. It was during this westward expansion, that all of the current territory of Ukraine came under Soviet control. The Soviet-Nazi alliance would last until 1941, when Hitler’s armies took over Ukraine to fulfill his colonial dream of Lebensraum. It involved extermination of Jews and other populations, resettlement within German agrarian colonies, enslavement of surviving Ukrainians and continuing extraction of grain, coal, and iron. The years 1941 to 1947 could be framed as a genocidal war between two imperial forces for the control of Ukraine as colonial living space. Both Soviets and Nazis had to confront a myriad of Ukrainian insurgencies, from nationalist to fascist ones. Territories liberated from the Nazis in Ukraine were “pacified” by the USSR through several massive deportations and ethnic celasning of communities deemed collaborators, such as the Crimean Tatars in 1944, and Galician Ukrainians, Boykos, and Lemkos in Operation Vistula in 1947.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the colonial violence inflicted on Ukraine was no longer genocidal, though the Russification policies remained in place until the mid 80s. In 1954, to commemorate the 300 years of the 1654 Pereiaslav Agreement, the Soviet Union transferred the Crimean oblast to the Ukrainian SSR. The nature of this gesture would come into question in 1991 and then again, tragically, in 2014. While Ukraine continued to be economically important for the imperial core, representing more than 20% of its agricultural and industrial outputs and constituting 25% of the USSR’s income, its relevance as a colony diminished in comparison to the Soviet Union’s new satellite states in Europe.

The countries behind the Iron Curtain were a geopolitical first for Moscow. Russia’s effective borders did not start at Curzon Line anymore but at the inner German border, right next to Hamburg and the Elbe’s estuary. For centuries, from the Kremlin’s perspective, Russia had been subject to several invasions from continental Europe: Poles, Swedes, French, and Germans. After 1945 and until 1990, Russia enjoyed strategic depth, which was helped by stationing around half a million Soviet troops in Poland, East Germany, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. In addition, the Warsaw Pact and COMECON countries provided the USSR a network of clientelistic states that depended on Moscow both militarily and economically, but they also composed an exclusive market for Soviet goods and commodities as well as for new sources of resource extraction.

The enactment of perestroika, glasnost, and federalist policies by Gorbachev in the mid 80s transformed the way that Moscow related to its peripheries within the Empire and with its satellite states. The restructuring, transparency, and decentralization processes enabled multiple “national questions” to reemerge across the Soviet Union, from Estonia to Azerbaijan and from Belarus to Kyrgyzstan. The Ukrainian question was probably the most delicate one. Historian Serhii Plokhy contends that Russo-Ukrainian relations were crucial for the continuing existence of the Soviet Union. Once the Ukrainian Parliament voted for independence in August 1991, later ratified in December with a more than 92% pro independence vote in a referendum, the fate of the “last Empire” had been decided. For Plokhy, though, while Ukrainian independence made it impossible for the Soviet Union to survive, it did not end Russian imperial ambitions, it just paused them for 20 to 30 years.

In fact, as Vladislav Zubok’s analysis of the USSR’s collapse shows, Yeltsin’s bid for Russian “independence” from the Union relied on the continuation of Moscow’s political, economic, and military control over the former Soviet republics. For Yeltsin, compromising on the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), offered a legitimate way to dissolve the Soviet Union but still maintain the Russian Federation’s (post)colonial ties with its near abroad. In addition, the CIS offered one way to institutionalize the economic, logistical, and infrastructural connections between the Soviet republics, particularly Russia and Ukraine. For both, the USSR had only reinforced their deeply interconnected industrial and scientific-technological complex. This also included the military, not only regarding the Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, but all Soviet strategic missiles and high-tech weaponry were constructed in Ukraine or required parts made there. The soon to be Russian armed forces were dependent on Ukrainian technology know-how, and Ukrainian labor depended on future arms requests from Moscow.

(Post) Colonial Clientelistic Dependency

It is in part because of such interconnectedness that the years 1992 to 2014 could be described as the fifth stage of (post)colonial clientelistic dependency. Ukraine was formally independent, but just like many other former colonies, it was politically and economically reliant on Russia. Mostly because Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity were at continuous risk of being trampled by Moscow. Kyiv worked quite hard and made sovereign sacrifices, before and after its independence, to achieve a “civilized divorce.” Even in the period leading up to the Ukrainian independence votes, both Yeltsin, representing Russia, and Gorbachev, representing the USSR, threatened Kyiv with officially declaring Crimea, the Donbas, and Southern Ukraine (former Novorossiya Imperial governorate) as constituting historical and integral parts of Russia that were just bequeathed to the Ukrainian SSR starting in 1922. Thankfully, Yeltsin’s power ambitions and Gorbachev’s hubris, along with their mutual animosity, prevented them from coordinating their anti-Ukrainian sentiments.

Kyiv had to accommodate Russian influence to survive as an independent nation-state. In 1994, the now infamous Budapest Memorandum provided assurances, by the Russian Federation, UK, and the USA, of respecting Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity and refraining from applying economic pressure or security threats, in exchange for transferring its Soviet nuclear arsenal to Russia and becoming parts of the Nuclear non-Proliferation Treaty. In 1997, in order to avoid a conflict with Moscow, Ukraine and Russia agreed on the Partition Treaty establishing independent national fleets, dividing armaments and bases, and leasing the naval base in Sevastopol to the Russian fleet until 2017. This was followed, the same year, by the Friendship Treaty bounding both countries to mutually recognize their sovereignty, territorial integrity within the existing borders, and mutual commitment not to use its territory to harm the security of each other. The treaty was ratified by Russia in 1999.

Their clientelistic relationship was not just determined by economic and technological integration, foreign relations coordination, and security considerations but also, by a kleptocratic symbiosis. Ukrainian transition to market-based economy, similarly to other post-Soviet states, was taken over by politically connected entrepreneurs who, through small capital investment but plenty of corruption, were able to get the majority of property titles of previously state-owned assets during their respective privatization processes. Because most of those enterprises, from banking to coal mining, and from agriculture to vehicle manufacturing, were by default, commercially, technologically, and financially, linked to Russia, the transition to capitalism resulted in Ukrainian oligarchs depending on Russian capital to reproduce their lucrative relations in exchange for influencing Ukrainian politics.

The metallurgy industry, for example, which dominated the Ukrainian economy, leading the country’s exports between 1992 and 2014 and represented more than half the Ukrainian budget, was almost entirely dependent on Russian gas supplies or transported through Russian territory. Fuel, fertilizers, and the entire electrical grid was controlled by Moscow. Contrary to Russia, at least since Putin’s first presidency, oligarchs in Ukraine have been deeply ingrained in electoral politics. Either through financing party politics or becoming elected officials themselves to avoid criminal prosecution and gain status and power. As long as Ukraine’s main exports were in the hands of the steel barons, such as Akhmetov, Pinchuk, and Kolomoiskyi, Moscow continued to dominate Kyiv by directly and indirectly buying elected officials. But Ukraine is not Russia.

If post-Soviet Russia isan example of electoral unitary authoritarianism governed by the siloviki, Ukraine, on the other hand, has enjoyed a degree of competitive electoral politics and developed constitutional foundations for a feasible democracy. The challenges to Ukrainian democracy are to be found in Russian (post)colonial clientelistic relation, in the massive socio-economic inequality and economic collapse produced during the 90s, and the “oligarchization of the economy.” However, it is precisely oligarchization that offered an escape from Russian influence. The bulk of privatizations of state assets and enterprises were carried out during both the administrations of President Kuchma (1994-2005). This continued in the administrations of Yushchenko (2005-2010), Yanukovych (2010-2014), and Poroshenko (2014-2019) as well. The diversification of Ukraine’s economy, due to an increase of global agricultural commodity prices, rising trade with European Union countries, and the emergence of a solid consumerist middle class thanks to available credit at low interest rates from a national banking sector fueled by external European borrowing, transformed its political system into a democratic regime influenced by pluralist authoritarian financial power groups. In this model, the executive behaves as an impartial broker that balances the different interests of the oligarchs and it’s free to rule if those interests are protected. Yushchenko, Poroshenko, and even Zelenskyy were able to both attend to the oligarchs’ financial interests and demands coming from civil society. In 2013-2014, Yanukovych tried to break the system by going the Lukashenko’s way and he failed.

The Maidan protests in 2004-2005 represented the first steps towards the breaking of a clientelist colonial relationship with Russia. President Kuchma did not use force against the protestors, and he eventually supported a new Presidential election, not because he was aware of the election fraud that triggered the Orange Revolution, but because, by then the steel barons, had competition from the likes of Poroshenko, Zhevago, Bogolyubov, Kosiuk, Yaroslavsky, Bakhmatyuk, and even Kolomoiskyi. While some of them still owned assets in the metallurgic sector, their largest investments were in agriculture, banking, media, and manufacturing; all connected to Europe either via export destinations, financial borrowing, or access to markets. It also did not hurt that their consumers and clients in Ukraine were among those that supported Yushchenko—who had been poisoned by the FSB during the campaign—as the legitimate winner instead of Yanukovych.

During Yushchenko’s years, Kyiv started to exit its clientelistic relation with Moscow by reinforcing political, military, and economic ties with Brussels plus revising certain corrupt privatization schemes that benefited the steel barons. This was also the moment of cultural decolonization, with, for example, promotion of the use of Ukrainian in public instead of Russian, the reinterpretation of official history regarding Russia’s and the Soviet Union’s actions towards Ukraine by declaring the Holodomor a genocide, and reframing Stepan Bandera and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army as national liberators. Ukraine even played with starting NATO accession negotiations.

From the start, the Kremlin tried to undermine Yushchenko, by threatening to shorten and eventually cut off gas supplies. With 80% of gas exports to the EU going through Ukraine, and 100% of its gas coming from Russia, Kyiv was under constant pressure from European countries like Germany to avoid policies that might upset the Kremlin. In January 2009, Russia, taking advantage of Ukraine’s precarious financial situation during the 2008 global recession, completely cut off gas supplies, blackmailing it to accept an increase in prices. The crisis lasted two weeks, during which Ukraine lost its revenue for transit fees and suffered a total industrial shutdown with hundreds of thousands of layoffs.

Even if the strong economic growth of 2004-2007 helped Yushchenko carry on many reforms, the 2008 financial crisis, and the ensuing Russian gas blackmail, decelerated the Ukrainian path away from Russian dependency. With the Eurozone in crisis mode, Russian banks started to invest heavily in the Ukrainian banking sector, which had been vacated by the Europeans after 2008. The goal was to spread political influence by creating potential debt traps that could force certain, non-pro Kremlin, Ukrainian oligarchs to be in alignment with Putin. In 2010, Yanukovych, Russia’s candidate, won the elections riding on oligarchic and public discontent.

Decolonization Interruptus

Yanukovych’s aim of transforming the Ukrainian political system into a vertical authoritarian one and having Kyiv become a Russian vassal state, like Lukashenko’s Belarus, started immediately. Yulia Tymoshenko, who headed Yushchenko’s government twice as Prime Minister and challenged Yanukovych’s presidential bid in 2010, was arrested, criminally prosecuted, and convicted for her role during the Russian gas blackmail. With less than three months in office, he signed the Kharkiv Pact with Russia that set lower, subsidized gas prices, and extended the lease of the Sevastopol naval base to the Russian Black Sea fleet from 2017 until 2042. Lastly, in 2012, he passed a law that made Russian the de facto official language of some Ukrainian regions.

But Yanukovych could not afford to pivot only to Moscow. While Russia was Ukraine’s main economic partner into the early 2000s, European Union countries, plus Turkey, India, China and others, rapidly gained ground in trade and foreign direct investment. Already by 2012, the EU had become Ukraine’s main trading partner, overtaking Russia. Agricultural products gradually became the largest share of value in exports by 2019. For Yanukovych and many oligarchs, the prospects of an association agreement with their largest trading partner was a no brainer. For Ukrainians, particularly younger ones, it represented a way out of corrupt politics and Russian clientelism.

It’s not surprising then that Yanukovych’s sudden rejection of the EU deal, right after issuing decrees adopting the agreement, triggered massive protest from Ukrainian civil society. Moscow had increased import tariffs on metallurgical products to pressure the steel tycoons, such as Akhmetov, to lobby for a comprehensive economic deal with Russia instead. The deal included an immediate capital infusion by acquiring $15 billion in Ukrainian bonds, with very hefty repayment conditions, lowering gas prices, and returning to a custom union with chances of future membership in the Moscow led Eurasian Union. Ukraine would have transformed from a clientelist dependent into a de jure protectorate state. Domestically, oligarchs relying on low gas prices and access to the Russian market would have reinforced their hegemony and Yanukovych would have cemented his vertical authoritarian ambitions.

Like in 2004, large sectors of Ukrainian civil society opposed authoritarianism and Russian colonial domination with massive protests in 2014. After severe repression and more than 100 casualties, Yanukovych fled for Russia. The 2014 Revolution of Dignity inaugurated the second period of decolonization in Ukraine. However, simultaneously, Ukraine was under assault from Moscow with the invasion, and subsequent illegal occupation of Crimea and the Donbas.

Both moves made strategic sense for Russia and needed to be accomplished quickly with an element of surprise, taking advantage of political turmoil in Kyiv. First, occupying Crimea and incorporating it into Russia precluded any chances of a new Ukrainian Government rescinding the Kharkiv Pact and demanding Moscow to abandon the naval base in 2017. Constitutionality of extending the lease had already been put into question back in 2010. For Russia, losing Sevastopol would mean relinquishing hegemonic power in the Black Sea and losing already limited access to the Mediterranean. Secondly, by starting a continuous war of attrition in the Donbas, Russia was effectively thwarting any chances of Kyiv joining NATO. Admission to the military alliance requires unanimity from all members, which was an impossibility, and the absence of ongoing conflicts. Lasty, from the Kremlin’s perspective, invading Crimea and the Donbas was a national death sentence for Ukraine that would have led to political disarray, economic collapse, and social unrest. The Minsk Agreements were a legalistic way to effectively curtail Ukrainian sovereignty by providing the Donbas with veto power in foreign policy and constitutional matters. Russia counted on a deeply demoralized Ukrainian society that would have opted to live under Russian colonialism instead of in a failed state. Moscow miscalculated, and not for the first time.

Ukraine went through two very difficult years in 2014-2015 and even a war scare in 2018, but Russian actions ended up by eventually consolidating Ukrainian nationhood and reinforcing its decolonization. The occupation of the Donbas was a huge economic blowback against the steel tycoons, who were the most avid Kremlin supporters. Their steel factories, coal mines, and petrochemical facilities in the occupied area were either shut down or forced to exclusively trade with Russia. Besides lacking legitimacy in the eyes of the public, their economic loss diminished their capabilities of influencing politics. The oligarchic sector, regions, and enterprises that benefited more from trade with the European Union acquired greater political leverage.

In addition, the moment Crimea was illegally occupied, and the Donbas invaded, parts of the two regions from where pro-Russian parties gained most of their support, were de facto cut off from the Ukrainian democratic electoral process, making it very difficult for the Party of Regions and its successor, the Opposition Bloc, to be competitive in national elections. Both Poroshenko and Zelenskyy were the first back-to-back presidential candidates to be elected with the goal of achieving peace without compromising on national sovereignty and democratic integrity. Nationalists and liberals found a common cause. Ukraine was even able to enshrine the aspiration of joining both NATO and the EU in its constitution in 2019. By invading, Moscow directly contributed to Kyiv’s Association Agreement with the EU as its largest trading partner and reinforced Ukrainian civil society and its political class’ commitment towards a strong democratic regime. Finally, it seemed, Ukraine would be able to leave the Russian Ark.

Ukraine is not Russia, but Russia cannot be a hegemonic power without controlling Ukraine. Since Russia launched this newest war, many accounts have been given about the reasons. Russia’s relationship with Ukraine has been colonial from the start and the Kremlin’s narrative of Ukraine being a Western anti-Russia invention was crystallized by Putin last July and in February before launching the attack. As we have seen, this imperial ideology is not new, and the so-called westernization process of Ukraine has rapidly progressed since 2014. There are certain recent triggers that could have tipped the balance in deciding to strike now.

First in January 2019, the official establishment of the autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, reestablishing Kyiv’s Metropolitane, was established. In April 2019 the Ukrainian Rada passed a law protecting the use of Ukrainian language and declaring Russian a minority language.

In Spring 2021, Russia had already amassed 120,000 troops along the borders of Ukraine to deter NATO from adopting closer military relations with Kyiv. But it was also a show of external coercive diplomacy to force Zelenskyy to commit to implement the Minsk Agreements and drop the Crimean question from any negotiations. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian judiciary arrested Putin’s ally Medvedchuk, whose three television networks had been shut down by Zelenskyy back in February. In July, the Ukrainian parliament adopted a law on indigenous peoples, which included neither Russians nor Ukrainians. This law made Putin compare Ukraine to Nazi Germany. Lastly, in August, Kyiv sanctioned several Russian entities and blocked Russian websites. For the Kremlin these policies were driven by far-right Ukrainian nationalists determined in erasing Russian culture and by a demagogic Zelenskyy aiming for reelection in 2023.

Another factor that could be considered are the strategic consequences from the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020. During the conflict, Russian armed Yerevan was forced into a military defeat by Turkish armed Baku. This was the first time that an outside power, plus a NATO member and old regional rival, had intervened in the Near Abroad. The effective use of Turkish fabricated and operated TB2 armed drones was decisive in achieving Azeri superiority. Ukraine received the first of those drones in 2019 and used them for military operations in the Donbas in October 2021. The close defense cooperation between Turkey and Ukraine was seen by Russia as an example of NATO further developing ties with Kyiv for offensive purposes against it.

However, the question remains, why invade? The conflict in the Donbas precluded Ukrainian NATO membership; Zelenskyy’s possible reelection could have been preempted with Russian active measures, bribes, electoral meddling, or assassination; Turkish drones might be tactically useful, but they do not win wars and they could have been taken out with targeted strikes. Ukraine is not a military menace to Russia. Though it might be a democratic one. Kyiv’s independence with an economy linked to Brussels and a democratic, functional, political system, represents a vital threat to Putin’s authoritarian system. Freedom, democracy, and possible economic prosperity in Ukraine would have eroded Russia’s regime in five to ten years. Protests in Belarus in 2020 and in Kazakhstan in 2021 were considered too close to home for Moscow. A more than viable democratic Ukraine would end up by unraveling Russia itself.

Therefore, like Hungary in 1848 and 1956, and Czechoslovakia in 1968, the Kremlin decided to invade to restore its colonial domination over Ukraine, to maintain its enfeebled hegemony in the region, and end Kyiv’s democratic experiment before it becomes successful enough to be emulated by Russian civil society. Regrettably, after years of colonial experience, Moscow seems to rely on Tsarist imperialism with Bolshevik methods to carry on this war. It seems that the original probable objective of a quick victory to decapitate the government and install a Quisling puppet regime was based on cherry-picked intelligence that assumed Russian forces would be welcomed as liberators, as was the case with the US invasion of Iraq. This is no longer an option, and a return to February 22nd, 2022, would not be acceptable for Putin either. What seems to lie ahead is a conscious, and even premeditated, elimination of Ukraine as a country and society. Russia seems to be willing to reduce Ukraine to a type of failed war-torn state to prevent it from completely decolonizing. Empires are fragile and tend to bleed to death in endless conflicts Ukrainians, on the other hand, will do what they have been doing for centuries: resist and fight. Ukraine will join the likes of Vietnam, Algeria, Indonesia, and Ireland in breaking the back of colonialism. Their resistance might achieve what others have been unable to do before: vanquishing the Russian Empire.

Emmanuel Guerisoli is a PhD Candidate in Sociology and History at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank comments, suggestions, and edits by Elisabeta Pop, Udeepta Chakravarty, Robert Kostrzewa, Benoit Challand, Andrew Arato, and most importantly Ihor Andriichuk, whose country is showcasing more than admirable scenes of resistance, solidarity, compassion, and courage in the face of brutal atrocities and extermination.

Originally published in Democracy Seminar.