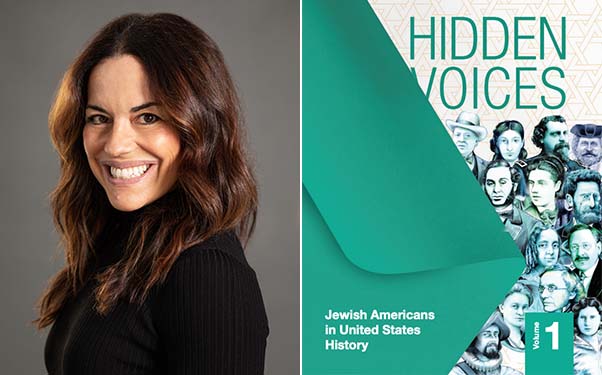

History Professor Natalia Mehlman Petrzela and NYCDOE Uncover the Hidden Voices of Jewish American History

When the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) approached Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, professor of history, to lead the development of the latest Hidden Voices curriculum guide, Jewish Americans in United States History, she was surprised they were considering her for the role. “My first thought was, ‘Great! I’d love to work on this project.’ But I quickly asked, ‘Are you guys sure? I am Jewish, I’m a historian, and I have lots of relevant expertise for a curriculum project in U.S. history, but I am not a Jewish studies professor.’ However, they let me know that they wanted to work with me because this project is about writing accessible essays and gathering primary sources about U.S. history, and bringing together scholars, experts, and NYCDOE staff to cover these topics in collaboration,” says Petrzela. “The fact that I wrote a book about and still research curricular controversies also helped.”

The Hidden Voices project was created by the NYC Department of Social Studies in 2018 to help students in grades K-12 learn about the numerous groups who are often omitted from traditional historical accounts of those who shaped history and identity in the United States. Currently there are guides on Muslim Americans—released alongside the Jewish American guide— LGBTQ+ Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, members of the global African Diaspora, Latines, and Americans with disabilities, with more under development. “We’re in a really disturbing moment in our country right now, where there is a strong movement against teaching about the diversity of our past and about some of the ugly ways that minorities have been excluded. I consider this to be part of the resistance to that movement. We’re giving a full picture of the diverse range of Americans who live here, have made their homes here, and have struggled with ugly forces in American history but have also embodied some of the best American ideals,” says Petrzela.

This project gave Petrzela a way to connect more deeply with the primary and secondary grades, as those working as university professors may feel somewhat removed from those grades. “This project was a great way to be involved in more direct curricular development,” says Petrzela. “It was important to us to not only have people who are experts but make sure they can write in an accessible and exciting way. In some ways, it doesn’t matter if you are the foremost authority on some particular person. It’s not a help if you are not going to write materials in such a way that a busy sixth-grade teacher can appreciate them and be excited about incorporating them into their curriculum.”

For the guide, Petrzela and her colleagues commissioned a collection of profiles and supplementary resources, primary sources, guiding questions, and profile essays of Jews in U.S. history that educators teaching social studies or history at any grade level can use to supplement their existing teaching. “It’s very common that the only time children in secular schools in the United States learn about Jews is either in Holocaust education or if some antisemitic incident happens—and then they’ll receive something more like a training,” says Petrzela. “Both of those things are very important, those interventions, but they are deeply insufficient to communicate the complexity and the importance of Jewish experiences in this country. This curriculum can at least be an important step in redressing that.”

Petrzela also hopes that the guide can help counter the increase in antisemitism in the United States. “To the extent that the rise in antisemitism that we are seeing right now is rooted, at least in part, in ignorance, this curriculum can help address that. Jewish history is a crucial part of American history, separate from Jews’ relationship to the state of Israel. We don’t shy away from Israel in this curriculum—you can’t talk about Jewishness in the United States without it coming up sometimes—but this is not a curriculum about the Middle East or about Israel. I strongly believe there are a lot of teachers and students and parents and professors out there who want to teach more about this group of people as a complicated, fascinating, and important group in American history but who may not have the resources to do so.”