A Menu of Flavors of Speaking

Hey, how are you? I hope you are doing okay during these strange and troubling times.

As for me, I’m doing well, considering. For instance, while so many people have lost their jobs, I have been fortunate to keep mine, as an Academic Coordinator and member of the Leadership Team at a private English language school in Peru. (We’re doing things remotely now, and the shift was a major undertaking, but we saved the school. Maybe I can tell you about that someday.)

Talking about my job: There’s a project that I’m working on, and I’m wondering if you can help me out. I’d like you to put your eyes on what I have and maybe give me some feedback. You’ll find my contact information down below. Promise to be nice first! Okay, thanks.

So, I’m part of a small team that is revisiting the curriculum here. Our program is a general language one for all ages, and right now it is pretty grammar-based, but we are trying to shift the focus a bit and become more attentive to development of the four language skills. You know what they are: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. My main task at the moment is to revise the course of study to better promote speaking proficiency.

This is a little more complicated than just ensuring learners have opportunities to talk, but you probably know that too.

The way I see it, I have to think about the kinds of speaking that people do, and also how we teachers can assess someone’s ability to do these various kinds of speaking so that we can help learners over time to build the necessary competencies. Easy peasy lemon squeezy, yeah?

Ah, but no. There are of course lots of speaking situations and functions, and there are lots of criteria for what it means to speak well. Ugh.

To get a handle on this project, I have been doing what I always do when I don’t actually know what to do: I’ve been reading. I’ve consulted books and articles by authorities in this area, and maybe you know some of the names: Anne Lazarton, Henry Widdowson, Janet Goodwin, David Bohlke. I’ve looked at lists of standards, like the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, and the Common Core, and TESOL International’s guidelines for PREK-12 and adult education. I’ve cheated too, by peeking at curricula used at other schools–shhh.

Oh, and every once in a while, just to change things up, I have also talked with colleagues–speaking about speaking. Emma, shouting you out! By the way, that sort of metaness–using language to communicate about language use–is one of the little pleasures I derive from our field.

And so but anyway, here’s a description of where I’m at with promotion of speaking proficiency. Don’t worry, I’m aware that I’ve already taken up a chunk of your valuable time. So instead of dealing with both the different kinds of speaking and also ways of evaluating speaking skills, I’ll just deal with the first one, saving assessment for a later piece, maybe. You’re welcome.

Right, so, flavors of speaking. To be brief (too late!–you say), an idea has tumbled into my brain about a way of categorizing these that has helped me get organized curricularly.

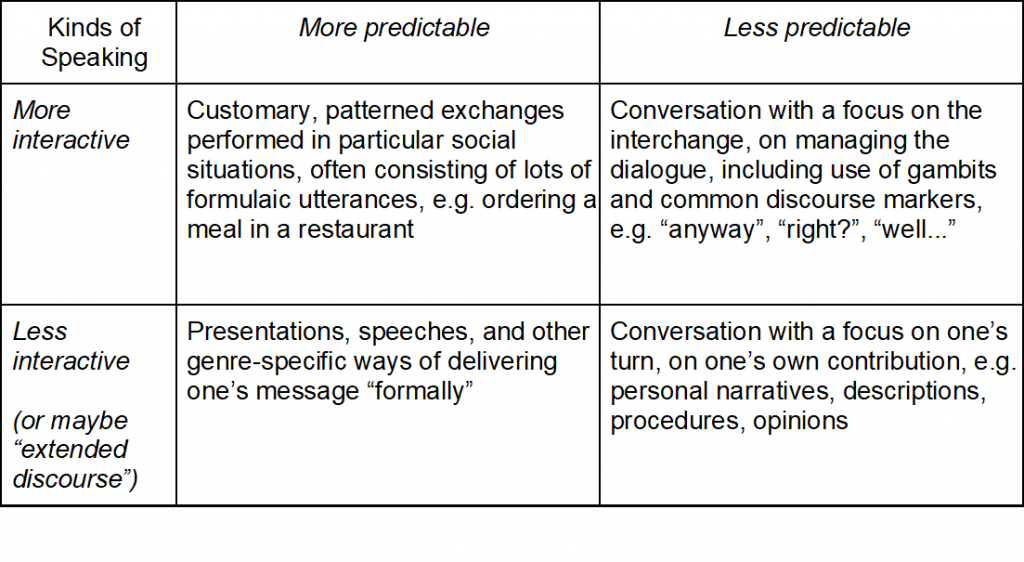

I’ve come to think about speaking as having two–what?; let’s call them dimensions.

One of these dimensions has to do with how interactive we are being. There are times when we are speaking and not being very interactive at all, like when we give a presentation at work or school. On other occasions, we are engaged in a rapid-fire back and forth with another party, such as when we run into an acquaintance on the street and are at the beginning of a conversation. The considerations around speaking are different in each case, naturally. For example, you don’t have to be all that concerned with knowing how to politely ask someone to clarify what she has said when you are the only one talking–but you do have to make certain you have the language to be clear yourself about whatever your topic is, and that you have organized your talk with a nod to clarity too.

The other dimension I think about when it comes speaking is how predictable the content is. Sometimes, in, say, a discussion you are having with a friend, subjects come up seemingly randomly–although, if you think about it, what you do with those subjects tends to fall into a set of communicative categories: giving an opinion (for example, about COVID-inspired governmental restrictions on your activities); telling a story (like your first kiss); detailing a procedure (such as your personal recipe for making an excellent egg salad). Other times, you can pretty much tell exactly how an exchange is going to go before it starts: when I am sitting in a restaurant, I am sure that at some point (hopefully soon!) someone will ask me what I want to eat, then I will tell that someone what it is (an egg salad sandwich, probably–I like egg salad), and then they darn well better thank me for my order!

So, categories of speaking, in two dimensions: level of interaction, and level of predictability. Hey, do you like tables? I like tables.

I’m still playing around with the verbiage, but hopefully you get the general idea.

And to connect this with curriculum: My notion is, in our school here in Peru–where we teach general English instead of English for specific purposes, as I said before–, if we instructors are “visiting” each of these “talk boxes” regularly in our classrooms, building learners’ knowledge and skills through generous input and plentiful opportunities for practice, as part of a larger program in which they are moving through the levels while we are gradually ratcheting up our expectations, fluency-wise, accuracy-wise, and complexity-wise; I propose that, if we educators are doing that, then we are helping our learners to become well-rounded, competent English language speakers.

Well, what do you think? To what extent does the table actually capture what it means to be a proficient speaker of English? And, if these talk boxes are, like, the destination for learners, what does the map look like? That is, what are the educational experiences that’ll get them there? Come at me with any ideas you have at tobillnelson@gmail.com. And remember, I said be nice!

A note on sources not linked in the article: Lazerton, Goodwin, and Bohlke contribute helpful chapters about speaking to Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (4th edition, 2014), edited by M. Celce-Murcia, D.M. Brinton, and M.A. Snow, and published by National Geographic Learning. Henry Widdowson’s Discourse Analysis (2007), part of the Oxford Introduction to Language Study Series, of which he is the editor, is a fine overview. TESOL International has a page on its website where you can purchase that organization’s publications about language proficiency standards.

Author’s Biography: Bill Nelson, MATESOL 2018, lives in South America. For the last few years he has worked at Extreme Learning Centers/Via Lingua Peru, where he teaches English, teaches people to teach English, and oversees teachers of English. His hobbies include running, watercoloring, and eating egg salad. Find him on LinkedIn.

About the author’s image: Self -portrait (Kamehameha pose). 2020. Watercolor, graphite, ink.