After Orwell: Some Thoughts on the Post-Pandemic World

by András Bozóki, Professor of Political Science, Central European University, Budapest and Vienna

COVID-19 is the first global ‘plague’ which will leave long-term marks and memories of quarantine, masks, gloves, curfews, mass death, economic decline, air travel disruption, loss of physical contact between people, i. e. social distancing, and systematic disinfection.

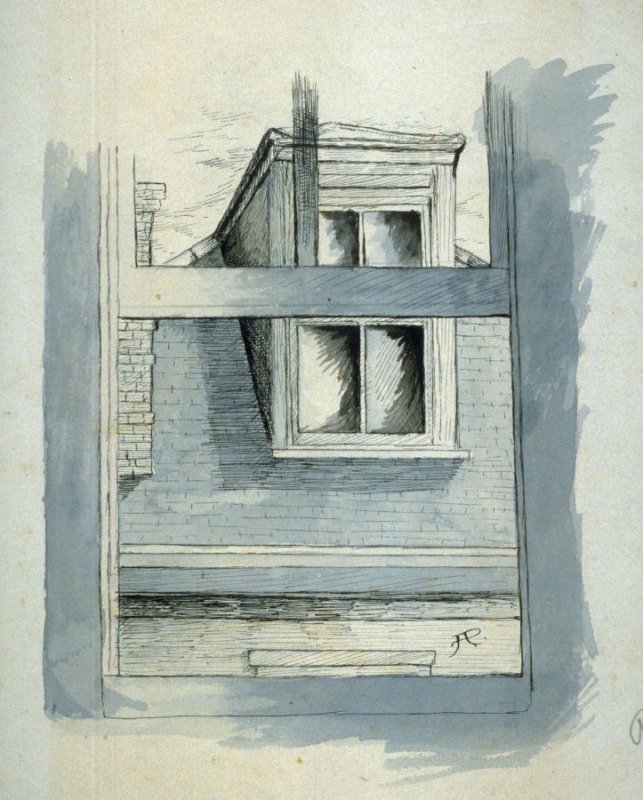

One of the most popular Facebook groups of this period is “View from my window,” which gathered one and a half million followers worldwide in three weeks. Everyone posts images from their homes, allowing us to take part in both private and global travel in cyberspace. We virtually look out the window of apartments in Alaska, New Zealand, and the Philippines. We peek through the keyhole. Another, even more intimate, Facebook group was the Hungarian “My home office challenge” group, in which everyone uploads a picture of their desk and the scene of their work at home. Here we no longer look from the inside out but show a corner of our apartment to the curious looks from the outside.

Entangled within National Tradition by Géza Komoróczy, a Hungarian historian, was published almost thirty years ago. In the digital age, we go further: we are being entangled within our interior. The sociological concept of glocalization, which combines and dissolves the global and the local, has become illustrative of recent online activity.

After the epidemic, it will not be the number of deaths but the memory of the shock that will prove decisive. The shock that forced everyone to radically change their usual behavior overnight. Part of this common experience is that the epidemic is ‘democratic’ in the sense that the virus does not discriminate: anyone can be its target, regardless of age and physical condition. It kills few, but frightens everyone, although the wealthy have a much better chance of defending themselves. While some have the privilege to move around in their private gardens, the majority remains stuck within the walls of their apartments.

Patients, the poor, those in vulnerable jobs and the elderly are most affected by the epidemic. Nurses, teachers and social workers, whose work is still barely recognized by society, are also more exposed to the pandemic. The vulnerable populations can find themselves in unbearable situations. These situations range from alcoholism to depression, mental illness and unemployment to starvation. Domestic abuse and violence may intensify, many may drop out of the education system, and the number of suicides may rise. In such moments, when there are changes in state redistribution policies, social solidarity can be measured. Then it becomes clear what a person’s life is worth to a community.

But why is coronavirus death different from other deaths? How many people die from circulatory and heart failure, cancer, flu, car accidents and military conflicts? How many pulmonary patients die and how many of them can be attributed to pollution? Compared to the current epidemic, even the AIDS pandemic experienced in the 1980s was negligible. Why do the deaths listed above bother the public less than the victims of the coronavirus? Why do some social events become trend-reversing historical milestones and others don’t?

Reality and its social construction overlap. The speed, invisibility, and global reach of COVID-19 are unparalleled. We are more afraid of the danger we do not perceive directly, because it is colorless, odorless, invisible, but can strike us at any time. The speed of its spread creates a sense of inevitability. When a sequence of events arrives in a wave-like manner, the interconnection of its individual components exponentially amplifies the effect. People who are forcibly locked into their homes face this external tsunami. The impact of the disease is exacerbated in populous centers with high density. The epidemic affects city dwellers more than the people in the rural areas. This has already been the case with plague outbreaks, although they have not yet become global.

The digital age, which was supposed to “set you free,” now makes you sick. The dystopian nightmare of biological warfare now seems possible, and public demonstrations by urban citizens can be dismantled with well-timed, centrally launched epidemics. Instead of water cannons, drones will be able to spray us. Guns are no longer needed.

Taken together, these factors — simultaneity, contagion, invisibility, globality, density, and incurability — together contribute to the socio-psychological effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

It will have a generational effect. The slowly declining “boomers” are being replaced by the “coronavirus” generation. I never thought it was appropriate to name generations with letters, like Generations X, Y, Z, because “generations” are defined by significant historical events that affect broadly equal social groups in a similar age. These events, which were of global significance, convey different cultural patterns to wider sections of society, and their impact can be felt for decades.

Researchers are competing over time to develop a usable vaccine as soon as possible. Despite their expected success, it can still be assumed that the epidemics sweeping the continents like giant waves will return. The concept of immunity used in peacetime is relativizing and will be valid in a narrower sense, for an ever shorter period of time. Isolation, atomization, and physical distance become social in scale.

That may not be the right answer. Prolonged isolation weakens our biological and social immune systems. Patients need to be segregated, but not everyone can be sick at the same time and not everyone can stay home. It is the job of healthy people to maintain the daily functioning of society: to work, to travel, and to have fun. The life of human society can be broken not so much by the disease, but primarily by ourselves: if we accept that we have fallen apart. For social beings, this is unacceptable.

The Hungarian government is not alone in failing to prepare carefully for the crisis. What is distinctive, however, is that government communication has consistently not been honest. Directors of the government’s propaganda machine have not been equipped to deal with the spread of the coronavirus, but have rather chosen to attack migrants.

The transition from conspiracy to reality did not go smoothly. The government did not blame the epidemic on the Chinese Communist leadership, but on two Iranian students in Hungary. The regime undermined public confidence by postponing tests, and people felt cheated and did not believe the official data. The state’s communication was riddled with secrets, censorship, and lies, which endangered human lives. More and more people have noticed that lies kill.

If nothing else, the regime quickly recognized the opportunities that could be exploited to accumulate power during the epidemic. With the Authorization Act, Prime Minister Orbán gave himself unlimited power. Mr. Orbán made all Fidesz MPs unanimously approve the state of emergency. This is, in principle, for the duration of the epidemic, but how long the epidemic lasts is determined by him, so his authorization is practically unlimited. Since the Romans, this has been called a system of command, or dictatorship. The term dictator originally meant “a chief official with extraordinary powers in the Republic of Rome.”

Orbán, the embodiment of this pathologically personalized system, believed that the best way to control the epidemic was to find scapegoats. In doing so, he revealed that he lacked not only professional respect for doctors and social workers, but also his ability to comprehend the problem. His “System of National Cooperation” is essentially based on the pillars of inequality and anti-solidarity. For example, the concept of a ‘work-based’ society is a tax haven for large investors but excludes the poor, who are left to fend for themselves.

We can be confident that after the epidemic, common sense will prevail in many countries and they will return to freedom. The importance of expertise, without which planning and public policy cannot exist, will be recognized even more than before. It will be important to note which countries return to normal democratic functioning and which leaders continue to maintain the state of emergency for as long as possible. Since Edward Snowden’s revelations, we know that some democracies collect data about their own citizens in an unconstitutional way. But nonetheless, we can only hope that the shock of the epidemic will help the fall of populist leaders in Western countries.

As time goes on, it is increasingly likely that the lives of societies will have to be restarted in novel ways. Decision-makers may recognize that new thinking is needed and that the crisis of each subsystem must be approached in a unified way. An environmentally conscious lifestyle can be strengthened, progressive taxation and intergenerational communication can be emphasized. If we recognize that unilateral globalization has a devastating effect in the long run, we may be able to make reforms that will allow us to live more solid, equal, and better lives after the crisis. Recent attempts at alternative globalization may steer social development in a more democratic direction.

In contrast, there is the other possibility in which authoritarian regimes, becoming dominant, consciously break away from liberal democracies. In these countries, restrictive rules, which were still considered temporary at the time of the epidemic, may persist. The culture of hypocrisy may be pushed into the background, and these systems may move to a pseudo-collectivist, command-and-control model based on the direct observation of citizens. Collectivism can be “virtual” in the sense that it does not have to be in a common space, in physical proximity to each other. It is enough for individuals in the online world to blindly follow the leader’s instructions, even in isolation from each other. When goals are replaced by tools, citizens’ behavior becomes machine-like, ritualistic.

Seventy years ago, Hannah Arendt thought that the two most important tools of a total dictatorship were propaganda and terror. Fifty years ago, Juan Linz believed that the most important feature of authoritarian dictatorships was depoliticization and the maintenance of traditional mentalities.

Foucault’s theory of the transformation of supervision and punishment rises to another level. In the past, punishment was public, and its purpose was deterrence, which is why it took place in public spaces in front of everyone. Later, it all moved to closed, total institutions, like state prisons. After that, the emphasis gradually shifted from punishment to prevention: positive state regulation of behavior, internalization of regulations, and adherence to the protocols of the system.

The main goal was no longer to punish the deviant offender, but to positively reinforce the behavior of the norm-following, conforming majority and to codify this pattern. Behavior regulation has already been addressed primarily in workplaces and schools. Even in the new situation created by the coronavirus epidemic, there is a motive to follow orders. But the state no longer aims to lock anyone in prisons and hospitals that are already costly to maintain. It’s easier to instruct everyone to stay home for their own sake. Room captivity is a new form of prison privatization.

Now, for the authoritarian systems of the digital age, propaganda and the atomization of society are paramount. Free discursive spaces aimed at learning about the situation disappear. The real danger is big data authoritarianism, where even the observers have no chance of observing who is watching them.

The state can classify its citizens according to whether they consider them to be behaving well or badly. This process has already begun in China. But the guardian-protective state is also increasingly curious about our thoughts. The information from which our thoughts sprout is manipulated by thousands of trolls. Members of the Orwellian Thought Police may not yet know what is going on in our heads, but it is becoming increasingly possible to explore this, based on our voluntarily published data on social media.

As the surveillance state sooner or later becomes the enemy of the citizens, a society that secretly defends itself against the sanctioning power of ‘thought crime’ may also emerge. Defense against the state’s ‘thought reading’ will be the only chance to preserve human dignity. If we do not have strong, alternative ideals, our daily actions will be guided by fear, hiding, and self-censorship.

But the state can not only trace our behavior and thoughts but can also classify us according to our state of health, on the basis of which, some will be considered more valuable than others. Health status is always determined by an individual’s physical fitness, so a bonus can only be given to obedient citizens who improve their loyalty rates through sport or other physical activity. The state-sponsored fitness culture – the Darwinian culture of survival of the fittest – is built on a cult of strength and flexibility.

In this culture ‘critical thinking’ would make no difference at all and would even be undesirable. A new tool of repression might be biopolitics, in which not only will our health condition become public, but the legal system will openly discriminate between us. If, from biometric signals, the state perceives someone to be ill, they can ban them not only from traveling but also from occupying public spaces, track their movement, or even instruct them to stay home. What do we do if the system presents us with a dilemma in which we have to choose between freedom and health?

As democratic herd immunity is slowly emerging against the bio-dictatorship introduced to protect our health, the regime may initially find countless supporters. Where the main incentive is political loyalty, the future for experts is risky. In difficult times, the professional expectation of them would be to step out of the dominant paradigm and take an innovative approach to solving problems. But would they dare to do it?

The epidemic will not change human nature, but man-made institutions can be used not only to restrict freedom but also to protect it. In Eastern Europe the concept of social distance is confused with the concept of social segregation. For many zealous mobs, a state-frozen society is the end of history. By this they mean that they have won, and liberal democracy is over. They do not think that “fear is the seductive power of goodness” and that the observed might eventually become observers.

Although dependence is always mutual, we should remember Sándor Petőfi’s words:

“Though ships bob on the surface

And oceans run beneath us

It is the water rules.”

András Bozóki is Professor of Political Science at the Central European University, Budapest and Vienna. His research interest includes political change, democratization and democratic decline, political ideologies, comparative East Central European politics, and the role of intellectuals. He has been a visiting professor at Columbia University, Smith College, Bologna University and several other universities. His recent book discusses the role of intellectuals in the transition to democracy before, during, and after 1989.

This piece was a contribution to the Democracy & the Pandemic Mini-Conference of the Democracy Seminar held on May 20-21, 2020.