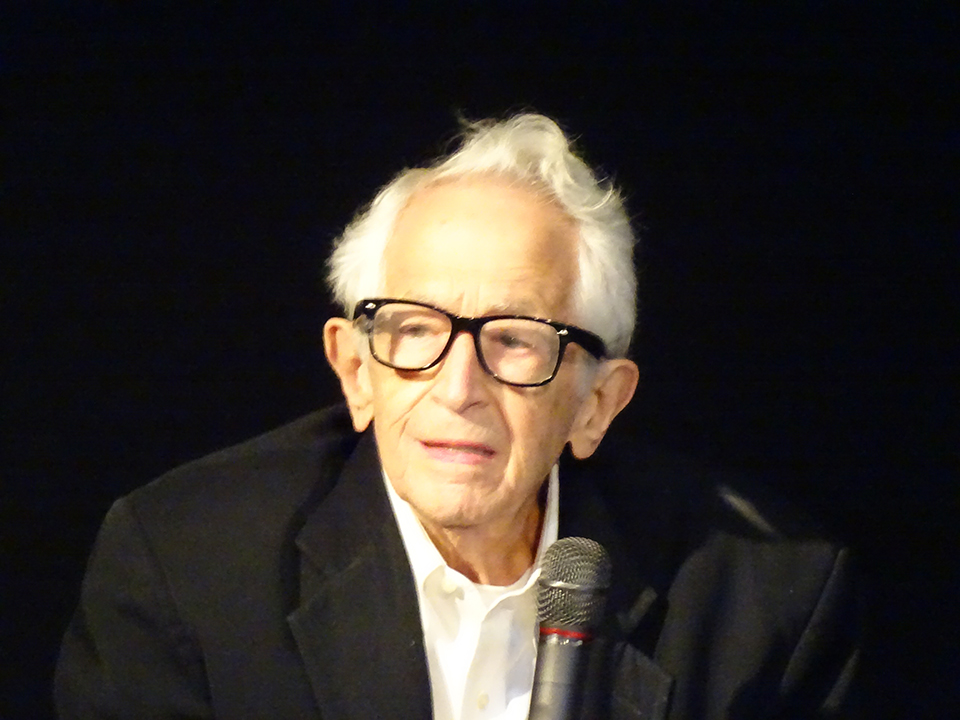

Remembering Richard Bernstein, 1932-2022

Richard Bernstein, great thinker, adored teacher, and a friend to so many, is no longer with us.

When I posted the sad news, I received spontaneous tributes and recollection from fond

admirers in the regions where we do our work. I realize that many people, including those who

knew him very well, are not aware of Dick and Carol Bernsteins’ exceptionally energizing

presence at our Democracy & Diversity summer institutes in both Krakow and Wroclaw. Their

striking intellectual generosity influenced our lives and opened up many paths to explore and to

follow. In this way Dick Bernstein is still with us.

I thought you might like to read the message sent to the members of our community, both

students and colleagues, by the dean of the New School for Social Research, Will Milberg. I

would also like to share with you some of the responses to the news of Professor Bernstein’s

passing from members of our transregional community. Since this is an open blog, we would

love to include your own reflections (please email them to tcds@newschool.edu), and we invite you to share your stories about Dick on this memory board.

In sadness and gratitude,

Elzbieta Matynia

From our alumni & friends

From Seyla Benhabib: Remembering Richard J. Bernstein

This piece was originally published in the Boston Review on July 11, 2022.

Returning from a two-week trip to Frankfurt on July 4, I found myself thinking about the opening session of a conference in honor of Richard J. Bernstein’s ninetieth birthday to be held in October at the New School for Social Research, where he had been professor of philosophy since 1989. I was on the program to introduce a conversation between Dick and Jürgen Habermas, my mentors and friends of the last fifty years. I was thinking of asking them how Hegel’s legacy was still present in their work.

I would have posed my question to Dick by first sketching what has now become Dick’s own distinctive legacy: “Hegel said, ‘philosophy is its own time comprehended in thoughts.’ For members of the Frankfurt School, including Habermas, this resulted in a critical theory of contemporary society, analyzing its pitfalls and contradictions with the goal of unearthing the potentials for an emancipated society of the future. I see Hegel’s legacy to be present in your work in a different way. You are a master at understanding immanently each Gestalt des Bewußtseins (shape of consciousness), at analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of each intellectual position, and at seeing how they must communicate with each other, even when each position assumes myopically that it alone has a monopoly on the truth. Whether you’ve been confronting the hubris of analytical philosophers to presume that they alone can think clearly and succinctly, or the self-imposed isolation of trends in continental philosophy such as hermetic forms of phenomenology and deconstruction, you have had an uncanny ability to bring them into conversation with one another. Would you agree with this characterization of your work?”

I would then have continued my dialogue with Dick: “In your early books such as Praxis and Action: Contemporary Philosophies of Human Activity (1971), The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory (1976), and Beyond Objectivism and Relativism (1983), you were concerned to emphasize how opposed positions would benefit from comprehending one another. Then you have engaged with the widest range of themes from rethinking radical evil, to assessing the roles of violence in the works of Carl Schmitt and Walter Benjamin, to reinterpreting Freud’s writings on Moses and Monotheism, and of course, to the magisterial rereading of American pragmatism with which you began your career—particularly the spirit of John Dewey. But I see Hegel’s spirit at work in each of these writings: you not only seek to make opposed positions see their inadequacies but in doing so, you also create a Zeitdiagnose—a diagnosis of the times, its pitfalls, dreams and illusions. Would you agree?”

Alas, I will never be able to ask this question and initiate that conversation. Dick died on July 4.

I first met Richard Bernstein in 1974 when, as the organizer of the Yale philosophy department’s graduate students’ colloquium, I invited him to give us a lecture. I knew very little about the so-called “Bernstein affair” of a decade earlier, when Yale denied the young and charismatic Bernstein tenure and much of the campus, including even its undergraduates, erupted in protest. The senior faculty in philosophy had managed to keep us in the dark about all that, and Dick told me the truth only in bits and pieces over the years. Surely, Yale’s treatment of him accelerated nearly twenty years of decline in a department that had once led the U.S. world of philosophy and that revived only in the mid-1990s.

In 1975 Dick invited me to the Dubrovnik Summer School in social and political theory. He and Habermas, together with Albrecht Wellmer and Charles Taylor, had revived the so-called Korčula School, where Ernst Bloch and György Lukács had met with oppositional intellectuals from countries behind the Iron Curtain. Dick already knew Mihailo Marković, whom he had invited to teach at Haverford and who at the time was the leader of the Praxis School of philosophy in Yugoslavia. Together with Marković, Habermas, Wellmer, Taylor, Agnes Heller, and his colleagues Sveta Stojanović and Zaga Golubović, Dick had formed the journal Praxis International in Spring 1981.

So it was that, in the presence of Bernstein and Habermas, in a small seminar room at the Inter-University Center in Dubrovnik, where the Praxis group met, I read my paper on “Rationality and Social Action in Max Weber’s Work,” which, whatever its other merits, began the deep mentorship and friendship with Dick that lasted half a century.

Upon finishing his term as co-editor with Marković of Praxis International, Dick proposed that I assume the position together with Stojanović, and I did so from 1986 to 1992. During the civil wars in Yugoslavia and the ensuing ethnic conflicts, it became increasingly difficult for the journal to continue in a non-partisan way. In a memorable meeting at the University of Frankfurt, Praxis International was dissolved and Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory, was established, which Andrew Arato and I edited for its first seven years, until 1997.

These tumultuous years also saw the emergence of the Polish Solidarnošc Movement (1980–1989), the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), and the transformation of Central and Eastern Europe, but Dick held our often-fractious group together. Many of us who had been members of the journal Telos—Andrew Arato, Jean Cohen, Dick Howard, Joel Whitebook, and myself—had regrouped around Constellations. Together with Heller, who had joined the New School as Hannah Arendt Professor of Philosophy in 1986, Dick kept alive the legacy of movements opposed to the “really existing socialisms” of that time.

No account of my friendship with Dick can be complete without noting the significance of Hannah Arendt for both of us. In 1996 we both published books about Arendt: his Hannah Arendt and the Jewish Question, and my The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt. At that time, news of Arendt’s love affair with Martin Heidegger colored many perceptions of her work and persona. Sensationalist accounts such as Elzbieta Ettinger’s Hannah Arendt/Martin Heidegger (1995) made it difficult to see the legacy of Jewish politics and traditions in her thought, which Dick and I were addressing. While Arendt’s observations about evil became dominant in Dick’s subsequent writing on her (as in his 2002 book Radical Evil: A Philosophical Interrogation), I turned to the question of statelessness and proceeded to work on the rights of others—migrants, refugees, and asylees.

In 2018 Dick wrote Why Read Hannah Arendt Now?, responding to the worldwide revival of interest in her life and work, including the several biopics that had been made of her, and the search by a younger generation for a new orientation in political life. Dick taught a course on Arendt during his last semester at the New School. In our last conversation, three weeks before his passing, he told me that he had been thinking about returning to Arendt’s work around the themes of narrative.

Dick’s commitment to the tradition of American pragmatism ran like a bright thread throughout his work. He favored Dewey over Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, a view he elaborated in The Pragmatic Turn (2010). Like Richard Rorty, whose classmate he had been at both the University of Chicago and Yale, Dick stressed American pragmatism’s critique of the spectator theory of knowledge and rejected the quest for the mind to mirror nature. Dick continued to engage with these themes by turning to the work of Pittsburgh philosophers such as Robert Brandom and John McDowell and increasingly by defending a form of Deweyian naturalism as opposed to the focus on language alone. His last book, to be published posthumously, is called The Vicissitudes of Nature: From Spinoza to Freud.

In 2004 Nancy Fraser and I edited a Festschrift for Dick’s seventieth birthday, Pragmatism, Critique, Judgment: Essays for Richard Bernstein. The list of contributors—Rorty, Habermas, Taylor, Heller, Jacques Derrida, Thomas McCarthy, Geoffrey Hartman, Carol Bernstein, Yirmiyahu and Shoshana Yovel, Joel Whitebook, Judith Friedlander, and Jerome Kohn—reveals not only Dick’s capacity to engage in conversations across genres of philosophy, cultural as well as literary criticism, and psychoanalysis, but also his extraordinary capacity for friendship and bringing people together. His public lecture celebrating Habermas’s ninetieth birthday in June 2019 in Frankfurt was dedicated to the topic of friendship, beginning with Aristotle.

I once asked Dick, during a dinner with friends from Berlin, whether the death of his older brother during World War II had left an emotional hole in his life. It may have been a bit too forward of me to ask, but it always seemed to me that there was a dimension in Dick’s capacity to hold family and friends together that originated deep in his soul. Among friends, we used to call him the “Rebbe,” who would often say, “now, now children, stop your squabbles; we are all in this together.” We have lost our Rebbe in New York, and a hole has opened in our souls as well. To honor the legacy of Richard J. Bernstein, we must not only continue as honest thinkers; we must also cherish friendship and share generously, as he did with so many of us.

Seyla Benhabib is Eugene Meyer Professor of Political Science and Professor of Philosophy at Yale University.

From Will Milberg, Dean and Professor of Economics, The New School for Social Research

I am writing today to share the sad news that Richard J. Bernstein, Vera List Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, passed away on July 4 at the age of 90. You can read his official obituary here.

As I wrote just a few days ago in his retirement announcement, Dick (as we knew him) was an iconic figure in the Philosophy department, at the NSSR and The New School, and in the field of philosophy in the 20th and 21st centuries. He was a premier philosopher of pragmatism, a particularly American branch of philosophy, and was also one of few philosophers able to clearly bridge continental and Anglo-American thinkers.

While he was known around the world, Dick was a son of New York City with an unmistakable Brooklyn accent. He was born here on May 14, 1932, and while attending Midwood High School, he met Carol, who became a renowned literary theorist at Bryn Mawr College and his beloved wife of 67 years. He studied philosophy as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, earned a Bachelor’s degree at Columbia University, and received his PhD from Yale University in 1958. There, he wrote his dissertation on John Dewey’s Metaphysics of Experience, commencing his lifelong association with Dewey and American pragmatism. He taught as a Fulbright scholar at Hebrew University, then as faculty at Yale and Haverford College before joining the Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science (now the NSSR) in 1989. Among his many honors and awards was an honorary doctorate from the University of Buenos Aires, given in 2018.

During his 33 years at The New School, Dick was a leader in both scholarship and faculty governance. He served as chair of the Philosophy department multiple times and was Dean of the Graduate Faculty from 2002-2004. Even after leaving these leadership positions, he continued to be a strong faculty voice, and, most importantly, was committed to academic openness, radical and critical thinking, and humanism in its best form.

This list of leadership roles doesn’t capture the liveliness of his intellect and his commitment to principle, combined with the empathy and warmth that he brought to all his interactions with New School colleagues and students. Dick maintained close personal and intellectual relationships with Hannah Arendt as well as with Jacques Derrida, Agnes Heller, and other renowned philosophers who link us from our origins as the University in Exile through today’s NSSR. Together with Heller and Reiner Schürmann, he helped usher in a new era for the Philosophy department at The New School while “keeping it connected to its intellectual and moral mission,” wrote former New School President Jonathan Fanton.

As a proponent of pragmatism, Dick believed in a dedication to truth in concrete life and in experience, pursued within a community built on mutual trust, and in finding resonance in diverse figures across the philosophical spectrum. This commitment was central to his work as both a writer and a teacher. It also undergirded his belief that philosophy must engage with ethical action — something he tried his best to live, from taking part in the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi to teaching with the Transregional Center for Democratic Studies’ Democracy & Diversity Institutes to, most recently, helping at-risk scholars as the seminar leader for the New University in Exile Consortium.

Among Dick’s many books are Praxis and Action: Contemporary Philosophies of Human Activity, Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis, The New Constellation: The Ethical-Political Horizons of Modernity/Postmodernity, and The Pragmatic Turn. In 2018, Dick received significant academic and broader media attention with the publication of Why Read Hannah Arendt Now?, his Institute for Critical Social Inquiry lecture, and his New York Times op-ed on the continued relevance of Arendt amid increasingly troubling political times. “Arendt’s lifelong project was to honestly confront and comprehend the darkness of our times, without losing sight of the possibility of transcendence, and illumination. It should be our project, too,” he wrote.

Dick’s courses — in particular his small seminars, which often centered on close readings of difficult single texts — were legendary, conveying philosophical detail and contemporary relevance with exuberance and energy. He was a challenging yet generous professor who created encouraging spaces in which students could think critically together, and a supportive doctoral supervisor who kept in touch with generations of alumni. Amid worsening illness, he taught through the end of the Spring 2022 semester; fittingly, his final courses were on American pragmatism and Hannah Arendt.

Dick was a consulting editor for and frequent contributor to NSSR’s Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, and his last journal contribution will appear in Volume 43, Issue 1. Dick’s final book, The Vicissitudes of Nature: From Spinoza to Freud, will be published by Polity Press in November. The Philosophy department will hold a conference in his memory on October 14, “‘The Role of Philosophy as a Public Good’: A Celebration of the Life of Richard J. Bernstein”; registration information to come.

I have been fortunate to have had Dick as a colleague since I arrived at The New School. I have fond memories of running into him on his way to class, gleeful about a lecture he was about to give. “Will, we’re discussing Hegel’s Science of Logic today,” Dick would declare. “Want to join us?” He was a supportive and trusted advisor who shared with me his experience as Dean, his commitment to faculty governance, and his savvy approach to university politics.

We send our deepest condolences to Carol, their four children, and their six grandchildren, as well as to Dick’s many friends and colleagues, present and past. At the NSSR, we have indeed lost one of our greats. We will be forever grateful that he touched our lives, and we will miss him profoundly.

Sincerely,

Will

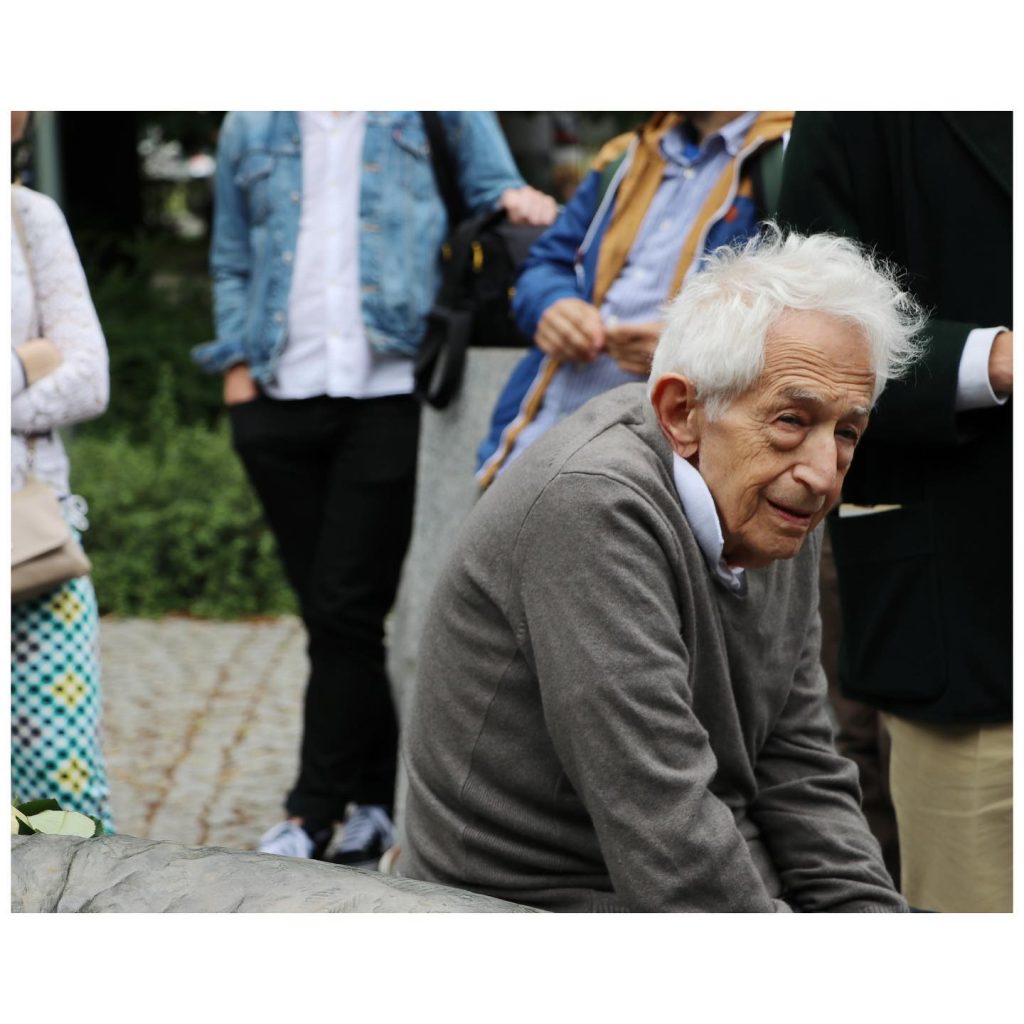

Richard Bernstein’s visit to Wroclaw in the summer of 2012 was an extraordinary experience. That summer Dick came for the first time as a faculty member of the Democracy and Diversity Summer Institute organized by Elzbieta Matynia and the Transregional Center for Democratic Studies at the New School. We both knew Dick from our studies at the Graduate Faculty, but it was not until he came to Wroclaw where we then lived and worked as academics that we finally got the chance to experience him as a teacher. His class on Hannah Arendt on which he gave us permission to sit was one of those rare expansive intellectual experiences when teaching swells beyond the classroom and consumes you in transformative ways. We remember how struck we were at the time by Dick’s selection of Arendt’s texts and their relevance for our political and intellectual worlds.

That summer was unforgettable also because Dick gave both of us very special presents.

Dick gave Lotar translation rights to his book, The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory, which Lotar published in Polish in the ULS Academic Press series that he edited. The public book launch attended by a large audience in the summer of 2016 featured a conversation between Dick Bernstein and Alice Crary and was connected to a Visiting Professorship award to Dick Bernstein by Wroclaw’s Mayor.

Dick also gave a very special gift to Hana who was taken by Arendt’s Jewish writings, and the way they spoke to the possibilities of political and social action under the conditions of shrinking democratic freedoms. We spoke on the subject with Dick many times during that summer, also during a very special dinner among friends around our kitchen table (see photo). After the last class that summer, Dick came up to Hana and told her he had a gift for her. He passed her a piece of paper with a photo-copied section of Hannah Arendt’s text. The text was a gift of an idea – the most practical thing in the world as Dick liked to say after Arendt. It was an idea written in difficult times for difficult times.

Thank you Dick, we will miss you very much.

From Hana and Lotar

Dearest Elzbieta, I want to say how sorry I am for your loss of Dick Bernstein. How lucky I feel to have spent two wonderful summer institutes with him in Wroclaw and to have seen him in New York. He was a wonderful teacher, and what I learned from him still stays with me. Here are a few photos. I love it that you and Dick are both in these pictures as is Agnes. I hope your recovery is going smoothly. we think of you and send much love. I am here if you feel at all like talking. Love Juliet

From Juliet Golden (TCDS alumna)

Yesterday the world lost one of its most brilliant philosophers— Richard J. Bernstein, Vera List Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research (NSSR). I got to know Dick through my work at the Transregional Center for Democratic Studies at NSSR. Dick was one of the most ardent supporters of the work we were doing at TCDS and taught many times at our graduate summer institutes in Poland, including his famous lectures on Hannah Arendt. In one of my photos Dick is wearing all black with TCDS Director Elzbieta Matynia and his wife Carol Bernstein in the city center of Wrocław where the Committee in Defense of Democracy (KOD) in Poland had called for a protest of a new law which would limit the autonomy of Poland’s constitutional tribunal. In another, he is joining students in a show of solidarity for the Black Lives Matter protests which were taking place in the US during the summer of 2016 due to the police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile in early July that year, just as our Institute was getting started in Poland. Additionally, Dick was a mentor to so many of our students and faculty and a great teacher. Dick, the New School won’t be the same without you.

From Adrian Totten (TCDS Program Coordinator)

We were deeply saddened by the news of the passing of Professor Richard Bernstein. As graduate students at the New School for Social Research in the 2000s and members of the TCDS network we had an opportunity to study with him and learn from him, and like so many of his students, we hold fond memories of these transformative encounters. Dick was one in a million, not only as a public intellectual of extraordinary acumen, but also as a warm, attentive and caring human being. His thought still influences our work, especially his account of radical evil, violence and his writings on difference and democracy. We recall conversations and seminar discussions that took place in New York, in Krakow and in Wroclaw and every one of them has left a trace. These traces went on to inform our research and teaching in subsequent years, in Philadelphia, Dublin and now in Lancaster, England. Dick’s influence will continue to reach as far and wide as his students are dispersed, in countless universities and other walks of life around the world. Our thoughts are with Carol, his amazing partner in the life of the mind. Our condolences to family, friends and the whole NSSR and TCDS community.

Karolina Follis (NSSR Anthropology PhD 2008) and Luca Follis (NSSR Sociology PhD 2009), Lancaster University, UK