We’re All in the Same Boat: A Democracy Seminar Update

by Jeffrey C. Goldfarb, Michael E. Gellert Professor of Sociology, New School for Social Research

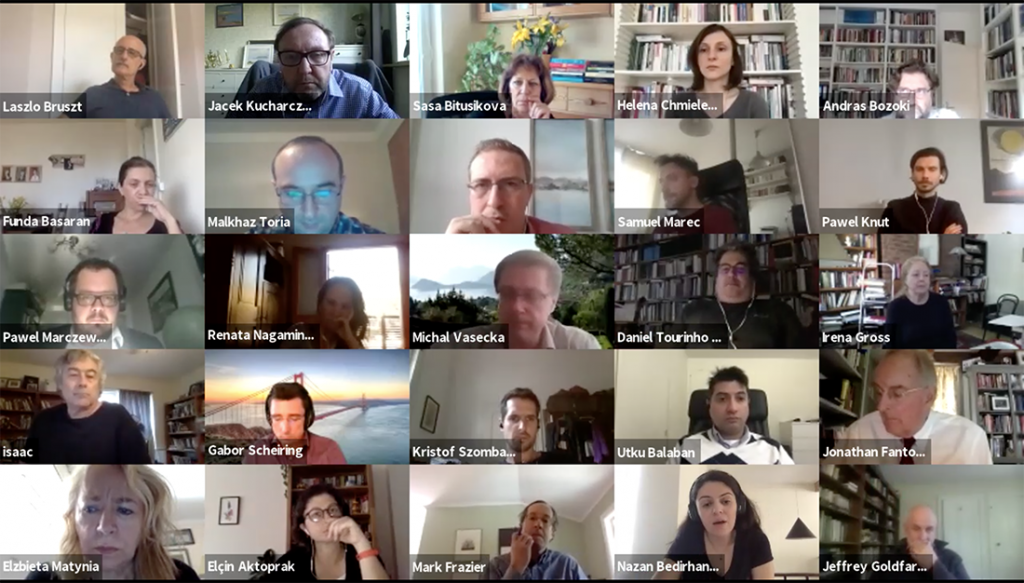

The Democracy Seminar, our worldwide committee of democratic correspondence, has moved to Zoom. Before the pandemic, last October, we held a conference in New York (see here for a report). We were scheduled to meet again this month in Wroclaw, Poland, but the meeting had to be postponed. In April, the seminar conveners—from Hungry, Poland, Slovakia, Turkey and the United States—discussed how we should proceed, and decided that it would be good to have a special mini-conference in May on the immediate problems democrats are facing in the shadow the Covid-19 pandemic. Posts here and webinars would follow on the problems and questions coming out of the mini-conference.

As I wrote over two years ago, when our current group first began to take shape, this is the second iteration of the Democracy Seminar. The first was an exchange between critical democrats in the United States and Central Europe in the late nineteen eighties and early nineties. The contrast between then and now is striking. The earlier group was made up of colleagues in Central Europe and the United States. Participants in the U.S. were critics of actually existing liberal democracies, who appreciated the work of democratic oppositionists of the Soviet empire, both as it spoke to the conditions under which they lived and our own situation. Participants in Central Europe were independent minded scholars, journalists and political activists, who appreciated Western critical thought and were creating an independent democratic cultural and political sphere in a politically repressive context.

Back then, our immediate situations were strikingly different on each side of the “iron curtain.” Now, we are all in the same boat. The papers prepared for the conference, and our discussions on Zoom all attest to this.

The May 20-21 Zoom conference: A Summary

Along with contributions from the established seminar branches, there were discussants from Brazil, Georgia, China, Romania and South Africa. We addressed a series of problems concerning the impact of the pandemic on democratic practice. The central question of the first day of the conference was: “How are the responses to the pandemic leading to de-democratization?” On the second day, we considered: “How is the de-democratization constituted and opposed?” (See the program at the conclusion of this post, with links to the working papers of the conference.)

1. We observed how authoritarians are using the pandemic to further their projects by both the enforcement of strict rules and the willful ignoring of the threat of Covid-19.

In Slovakia, enforcement of pandemic restrictions has extended the ruling powers, cynically coopting an emerging popular democratic movement against corruption, turning it from a democracy to a populism with a distinctively Slovak face. Beyond the law, the public health authorities have restricted public life, while through the use of conspiracy theories, civic associations and social movements antagonistic to those in power are being attacked.

In Georgia , there is a similar end through more selective means. The authorities have used the pandemic to strengthen the ties between religious and political authority, by selectively enforcing social distancing. Secular life has been paused, as religious life proceeds.

Strict social distancing enforcement has been used in Hong Kong to repress democracy protests.

In contrast, in Brazil and the United States, authoritarian leaders have attempted to use the official response to consolidate power through the intentional, even stylized, ignoring of the public health crisis. Concern about the pandemic is framed as opposition to the regime and even to “the nation.” Purportedly, only effete elitists worry about public health. And journalists, and even scientists and intellectuals more generally, are often targeted as “enemies of the people.”

In Turkey and Hungary, the responses extend already existing official public policy, combining repression and willfully ignoring the dangers of Covid-19. In Hungary, Gabor Scheiring maintains: “There is a discernible policy logic behind the government’s responses, that fit well into its socio-economic strategy that unfolded over the past decade.” Nazan Bedirhanoglu’s analysis suggests that this is also the case in Turkey. “Erdogan uses this pandemic as a political opportunity, as he always does whenever the country goes through social, political, or economic crises … he has a two-pronged strategy. The first component is to keep the economy moving no matter what. The second component is to distort reality in order to cover up the public health failure.”

But, there are limits to authoritarian responses, as the suffering from the virus and the economic consequences of the pandemic and the official responses to it are unequally experienced. Thus, for example, in Poland, “the torn mask of social solidarity,” as Paweł Marczewski puts it, is becoming starkly evident, with possible significant political consequences in the Presidential elections.

2. We saw authoritarian and democratic innovations in all of our countries, with variations on common themes.

As authoritarians work to extend their already existing projects under the cover of the pandemic, they are inventing new methods to prevail. Their democratic opponents are working to do the same.

Turkey is in a kind of cat and mouse battle with the European Court of Human Rights concerning the detention of political opponents. As charges are challenged by the court, new charges are invented, maintaining the imprisonment of opponents, before, during and likely after the pandemic. Such repression has been sustained through creative economic slights of hand, e.g., public banks provide state-sponsored credit, reinforcing securitization during the country’s 2018-2019 crisis and now during the Covid-19 pandemic, making it possible for the Erdoğan regime to intervene into the financial markets without public debate and accountability, as Ali Riza Gungen reported to our group.

A dystopian authoritarianism is on the near horizon, Andras Bozoki maintains, looking closely at Hungary, but also looking beyond its borders: the possibilities of biological warfare are being revealed, as a peculiar authoritarian combination of intensified surveillance and purposively ignoring the threats the virus constitutes new authoritarian forms. Instead of attacking the virus, the new authoritarians are attacking migrants, with a difficult transition from conspiracy to reality, using the viral threat to justify emergency measures determined by the will of authoritarian leaders, who classically meet the definition of dictator, using the pandemic to find scapegoats, justifying a surveillance state, focused not on monitoring social behavior that spreads the disease, but on thought crimes that challenge authority.

In China, online “thought crimes” that reveal the lie of the official story of the pandemic are severely attacked, not only by the authorities, but also by online civil society. Thus, there is the tragic example in the conflict between a sixty-five year-old writer and a twenty year-old female rapper: a writer who modestly recorded her life during the pandemic under siege and a nationalist rapper. I think this odd battle has rich implications for democracy. On the one hand, nationalist policies of the Party State are being extended in popular culture, but on the other hand, a modest online diary is keeping an open public life alive, and has not been silenced. An opening is being constituted against all odds.

Innovations in repression and resistance are present in Poland. On the one hand, ultraconservative anti-gender actors and right-wing populists are extending their opportunistic synergy, as Elżbieta Korolczuk names it, using the anti-pandemic measures to shield them from electoral and civic action challenges. On the other, new forms of protest and resistance against this synergy are being developed, as in in protests against the escalation of the already highly restrictive anti-abortion law. Not able to protest as they did in the past to resist these changes, with demonstrations in the hundreds of thousands, protestors are sustaining pressure by “hanging banners and slogans on private balconies and in windows, car blockades in the centers of major cities in cars and taking part in so-called “queuing protests,” standing in line at centrally located squares and near the Polish parliament, and email campaigns, sending millions of critical messages to the parliament.

LGBTQ+ activists are once again struggling under the most dire circumstances in Poland, a country in which towns, cities and entire regions are declared “LGBT free zones,” legitimating violence and rampant hate crimes. Faced with this, drawing upon the LGBTQ movement from around the world, particularly the successes of ACT UP, Polish activists have developed strategies to disrupt their own demonization through acts of “meaningful solidarity,” as Judith Butler puts it, with all those who are exposed to and suffering from Covid-19, i.e. everyone. Pawel Knut reported that in their meaningful gestures of kindness, supporting the healthcare system, addressing problems of hunger and homelessness, LGBTQ activists are fighting for decency and dignity for themselves and others.

This struggle for decency has become especially acute during the pandemic. Along with authoritarianism and Covid-19, there is also a pandemic of domestic violence. Stay at home orders are deadly for those in abusive situations; ways out are essential. Democracies address this with more (e.g., France) and less (e.g., the U.S.) success, while authoritarian regimes largely ignore the problem as they use the pandemic to attack “gender ideology” and the LGBT agenda in the name of traditional values and religious freedom.

And in regions, towns and cities, there is a new democratic awakening. In Poland, Hungary and Turkey , towns and cities have become bases of opposition to de-democratization. Ironically, in Turkey and Poland, the original powerbase of the present ruling regimes were in major cities, and now these same cities are the grounds for those who oppose the ruling powers. Indeed, solidarity against the pandemic and against outside authority that is viewed as illegitimate have been consolidated in localities. Despite systematic efforts to undermine them, such bases of opposition persist in Turkey, while in Hungary such systematic efforts seem to not only undermine a potential base of opposition and help the central authorities to balance their budget, it also seems to serve an ideological function: opposing the so-called “work based society,” as the alternative to the European welfare state.

3. As we analyzed how democracy is challenged using institutionalized democratic means, we considered how imagination supports both the constitution of authoritarian power and resistance to that power

Around the world, the institutions of democracy are being manipulated, and transformed, by the enemies of democracy. The new authoritarians come to power not via revolutions and military coups but through elections, sometimes rigged, followed by executive orders and legislation that undermine the constitutional order. Because this is happening or threatening worldwide, we are, indeed, all in the same boat. We observed how this has been an issue in the elections in Poland, Turkey, Brazil, Slovakia, Hungary and the United States. That democracy itself is at stake in elections in so many places, including the United States, reveals the clear and present danger. The principle and practices of democracy are on the ballot. Jeffrey C. Isaac, in his presentation to our seminar, demonstrated in fine detail how this is operating in the United States. Given the pandemic, will all eligible citizens be able to vote? Will our authoritarian, Donald Trump, who seems to have dedicated himself to proving that it (Fascism) can happen here, accept election defeat? These questions lead Isaac to underscore the importance of fighting for a free and fair election and for the defeat of Trump and Trumpism.

While the new authoritarians have much in common, some have more in common than others. The political performances of Slovak President Matovič, for example, are remarkably similar to those of Donald Trump, even though when Matovič personalizes politics and attacks democratic institutions, he favors Facebook, while Trump prefers Twitter.

As the conference proceeded, and I listened to reports from elsewhere and to the way that colleagues often compared their situations with the ongoing American travail, I had a strong sense that the U.S. was once again the first among nations, but not in a good way. I also realized again how much I have to learn about my situation by working with colleagues from elsewhere.

As we described to each other the nature of the authoritarian threats and considered ways to resist the authoritarian trends, two classic essays from Central Europe came to my mind: Vaclav Havel’s “Power of the Powerless” and Adam Michnik’s “The New Evolutionism,” both written in the mid 1970s. Havel demonstrates how appearing in public in support of the totalitarian regime legitimates it, and how a simple act of not appearing to support the regime would radically undermine it, as he dramatically put it: when a green grocer chooses not to put up the sign workers of the world unite along with the fruits and vegetables in his shop window. Michnik puts Havel’s position into a historical context: if people acted as if they lived in a free society, their actions would themselves create a free society, bounded though that may be. These essays accounted for the democratic oppositions emerging in Central Europe at the time they were written, and pointed to the power of the Solidarnosc movement in the 1980s. I admired these texts and applied their political implications beyond Central Europe with focus on 9/11 America in The Politics of Small Things.

But there is a dark side to the power Michnik and Havel illuminate, made apparent during the pandemic, described in Dagmar Kusa’s presentation at the conference. When we act as if democracy, socialism and freedom are real, even when we believe and know that they are not, they are emptied of their normative power, and ideals become even more remote from reality. Acting as if Slovakia is a normal democratic country, when a corrupt and repressive leader uses the pandemic to cover up corruption and to escalate repression, weakens the prospects for democracy.

As I am completing this report, Donald Trump has just given his Mount Rushmore Speech. It was the speech of a dictator, declaring war on all Americans who don’t support him, on all who identify with the Black Lives Matter movement, on those who are concerned about the pandemics of authoritarianism, the coronavirus and white supremacy, on those who question the official public commemoration of the traitorous leaders of the Confederacy and of those who enslaved others. To act as if Trump is a democratic leader and as if political leaders who look away from his authoritarian transgressions are normal democratic politicians, to act as if this upcoming election is a normal democratic one, is to be complicit in the destruction of democracy in America.

The responsibility to resist this destruction of democracy in the places where we live, and a common project of mutual support for the global defense of democracy, are the guiding principles of our seminar.

In the weeks and months ahead, we intend to further develop this common project.

We built on the May discussion in a webinar on July 14: “Democracy in a Time of Plague: Challenges and Opportunities in the Struggles Against Authoritarianism, Covid-19 and Racism,” trying to follow up on Trump’s authoritarian celebration of American Independence Day with a deliberate democratic discussion on Bastille Day. And we will continue publishing papers presented to our seminar in the coming weeks and months. Also look for the video recordings of the May conference soon, and for regular topical webinars from our worldwide committee of democratic correspondents.

Our Democracy Seminar, with its link at Public Seminar, is a constant work in progress, as is democracy itself. There is still much to be done.

See Conference Program and Conference Participants.

Jeffrey Goldfarb is the Michael E. Gellert Professor of Sociology at the New School for Social Research. He is also the Co-Executive Editor of Public Seminar. His work primarily focuses on the sociology of media, culture and politics.